Paying for Environmental, Social Change

For anyone living or working in London in the past year, you would have to be asleep at the wheel if you failed to notice Extinction Rebellion’s (ER) environmental protests or failed to see the impact of debate about food banks, universal credit and any number of other social issues in the UK election.

Changing our world has itself become a big business. Depending upon which side you are on, the mechanisms for change are increasingly sophisticated. And in general, we no longer rely on government to lead us through necessary changes. In many cases, it is corporations taking the helm, whether in concert with governments or ignoring them entirely.

Back in 2017, 232 major global companies, worth around $6 trillion, committed to cut carbon emissions with the aim of maintaining temperature change to two degrees or less. While the US government itself pulled out of the Paris Climate Accord, businesses increasingly see the need for an alignment between their interests and those of their consumers and their employees, not just their shareholders. Does this mean that earning returns is no longer a company’s primary purpose? Not at all. But they are becoming aware of threats to long-term sustainability of their enterprise.

This move has a very significant bearing on executive pay and incentive pay design. The decisions executives take, like the decisions those 232 companies made, matter greatly in this dilemma. After all, we know executives do what they are paid to do. That is why long-term incentives exist, and why key performance indicators (KPIs) are painstakingly set and agreed upon at the beginning of every fiscal year. Enter the era of ESG metrics.

In a recent report from Glass Lewis on sustainability metrics, 35% of S&P 500 companies included at least one environmental, social and/or governance (‘ESG’) measure in their 2018 incentive plans. As you might expect, energy, materials and utilities sectors have the most ESG measures and safety is the most common ESG measure currently used, followed by diversity. Currently, ESG measures are most often included in short-term incentive plans rather than in long-term incentive plans.

In the FTSE 100, we see about two-thirds are using some form of ESG metric in their incentive plans with about 60% incorporating them in the annual plan and 11% pulling them into the long-term plan. Their impact, though, is often muffled. ESG measures can lack a specific weighting in the overall incentive plan and just be included as one of a number of broad objectives against which senior management are judged as a basis for assessing annual incent payouts.

But not always, and this is a vital trend as ESG measures take on greater importance among other metrics.

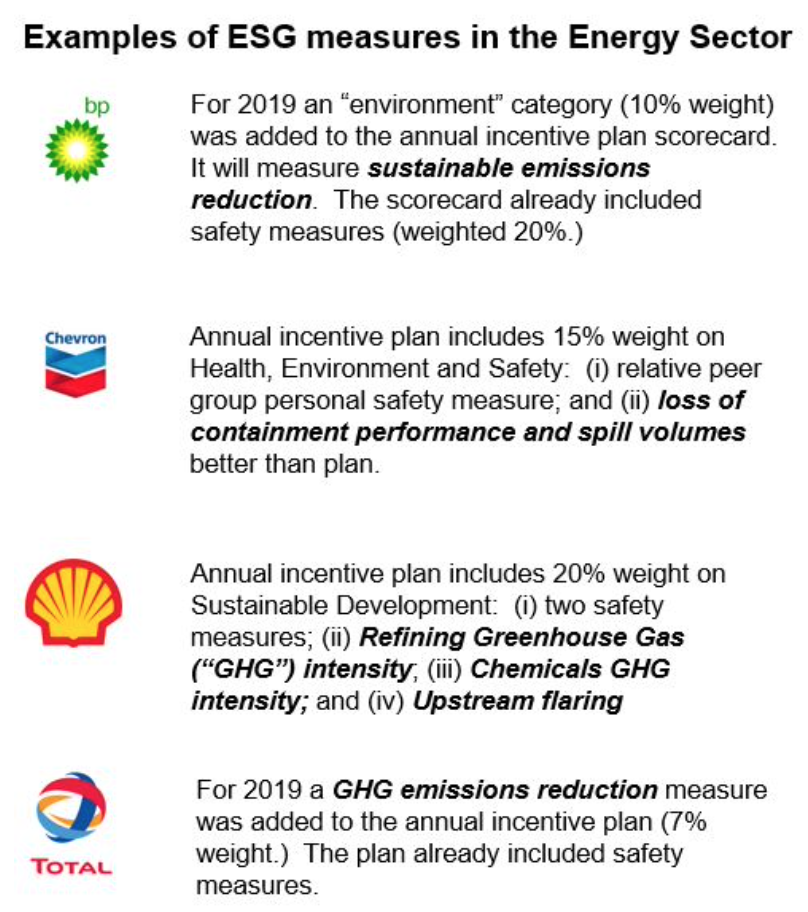

Let’s take the Oil and Gas business as an example. Companies such as Shell, BP, Chevron, and Total are all now introducing some form of ESG measures—with an emphasis on the ‘E’—into their senior management incentives. These are specific and measurable requirements that executives find ways to reduce the flaring of excess gases and reduce carbon/greenhouse gas emissions before any pay-outs are made. This is powerful.

The same action is taking root within the ‘sustainable energy’ sector. Take lithium mining as an example. Lithium is a vital component of the batteries going into the electric vehicles which will, many hope, replace the petrol- and diesel-fuelled vehicles in the future. But what does it take to get lithium? Some will argue that local lithium mining operations in Europe (Portugal and Germany, for example) will eliminate vast tonnes of CO2 emissions by reducing the need to ship lithium from China, Australia and Latin America and by supplying this vital material for electric vehicles. But others argue that getting lithium is not a ‘pretty’ process at all, and involves stripping top layers from large tracts of desert or requires large amounts of water to be used, thereby removing it from the drinking water supply.

The ESG measures Lithium Mining companies choose to employ in incentives are directionally very important, and the weight placed upon them tells you a great deal about the board’s priorities.

The lesson emerging for remuneration committees is that ESG metrics are not just a ‘bolt-on’. They now measure a central part of the executive role, providing the ‘license to operate’ from society as a whole and holding senior individuals to account in a way that no protest movement ever could. As much as Greta Thunberg may wish for our world to clean up its act straight away, the ugly truth is that it will take time and money. Right now, it is those executives in the industries which produce the carbon emissions the plastics and so on who hold the power now to flick the switch.